With the 24/7 cable news coverage of ISIS and terrorism, there has been a lot of loose talk about what Islam does and does not teach. However, much of this banter comes from people who have no idea what they’re talking about. This yields uninformed discussions and misinformation about how the Islamic texts direct the actions and lives of the ummah, the global Muslim population.

The level of ignorance, particularly here in the United States, is somewhat understandable – the media does a very poor job of explaining in plain language to a largely Christian or secular population just what Islam is (because the journalists themselves don’t usually have much knowledge of the faith). Who am I to say anything? Well, in addition to my work with Muslim communities and time spent in the Middle East, I wrote a 150-page historical analysis of the origins of Islamic prayer (which I’ve heard is an excellent sleeping aid), and I taught the secular study of religion at the university level.

Secular study means we do not approach a religion from a point of “truth” or personal belief, but instead, with as much objectivity as we can muster, we strive to understand each religion on its own terms. As we head into the holiday season and many Americans celebrate their religious traditions, it’s worth taking this fleeting awareness of religion overall to inject a little knowledge and understanding into what is a very important conversation.

And so I ask you to do what I used to ask students to do when they came to class: set your faith aside for a little bit, and try to think about religion in a neutral, non-judgmental way.

Where Did Islam Come From?

Islam’s prophetic figure, Mohammed, was a merchant before he was a messenger. He came from Mecca, which at the time was a stopping point for the trade caravans that led north to Palestine/Syria. More importantly, however, Mecca was considered a holy place, a neutral gathering point where fighting between polytheistic indigenous tribes was forbidden by local custom.

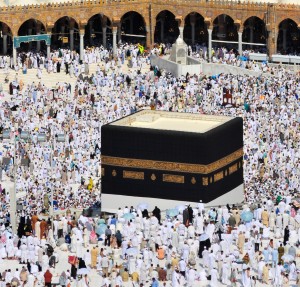

You may have seen photos of the large square black cube in Mecca around which Muslims walk and pray during hajj, a religious pilgrimage. It’s called the Ka’ba, and that box, in some form, existed before Mohammed. It was always a religious object, in which the indigenous tribes would place icons of their patron deities, symbolizing the conflict-free nature of the city.

You may have seen photos of the large square black cube in Mecca around which Muslims walk and pray during hajj, a religious pilgrimage. It’s called the Ka’ba, and that box, in some form, existed before Mohammed. It was always a religious object, in which the indigenous tribes would place icons of their patron deities, symbolizing the conflict-free nature of the city.

The Arabian Peninsula at this time was home to an array of religions. There were the indigenous beliefs of the tribes that lived on the peninsula. There were many Jewish tribes practicing different versions of Judaism. There were Zoroastrians from the Persian Empire to the northeast, and Christians from the Byzantine Empire to the northwest (as well as monks of various Christian traditions).

As Mohammed grew older, he became increasingly philosophical in his thought. He spent many hours and days away from the city, meditating and thinking. Tradition says that during one of these contemplative instances, the Angel Gabriel came to Mohammed and said, in so many words, God has a message, and you’re going to be the messenger.

The story goes that after a fair amount of skepticism, Mohammed ultimately accepted his calling, and he began to repeat the messages he heard. The first messages were short, somewhat general and focused on the notion of monotheism. These suras, as they’re called, make up the Qur’an, which is considered by Muslims to be the literal word of God and not a theological teaching from Mohammed himself.

How Did the Muslim Community Start?

As Mohammed set about communicating the messages to the people of Mecca, a couple things happened. First, a small but devoted group in the city embraced this new message. Second, the ruling tribe in Mecca did not like that. The Islamic message flew directly in the face of their polytheistic religions. As such, over 12 years, the new adherents to Islam trickled out of Mecca to safer places, and in 622, Mohammed snuck out of Mecca at night to avoid assassination by the ruling tribe. He and his followers traveled north, to Medina.

In Medina, Mohammed encountered tribes in conflict, and he served as a mediator between the tribes. In that mediation, we see one of the first examples of a political outgrowth of what Mohammed was reciting. He drafted what you might call a constitution for Medina, outlining the relationship between the Jewish and Muslim people in the city, establishing processes for maintaining peace and dividing authority. And it was here that Mohammed delivered longer, more robust suras with far more information about how to follow and understand Islam.

Every tribe on the Peninsula at that time used warfare as an expected part of trade and movement. In the United States, we litigate. In the 6th and 7th centuries, conflict resolution was substantially bloodier for everyone. As the population of Muslim believers grew, they naturally accrued a sizable military force, one that could pose a threat to the ruling tribe in Mecca. When Mohammed led his followers back to Mecca, the city surrendered and dramatically swelled the number of believers who, in some cases, weren’t offered much choice in what the city religion would be going forward. (For the interested reader, check out the prosthelytizing activity in ancient Israel that occurred more than a millennium before Mohammed. Not much choice there either. Likewise, Constantine did not provide his subjects a choice when he declared his empire Christian.)

After the conquest of Mecca, the community of Muslims grew rapidly, and alongside this growth, the Persian and Byzantine empires, exhausted from constant war, left a power vacuum in the region. The unified tribes on the Arabian Peninsula, with their newly acquired belief system, filled that vacuum. It became an empire governed by a religious tradition, just as the Persian and Byzantine empires had operated before it.

Is a Religion that Presents a Political Structure Dangerous?

Today, those warning of the inherent threat in Islam fret, “it is a political system as well as a religion!” Well, that’s true, and it’s true for the other Abrahamic traditions as well (even Christianity). Something that’s not easy to wrap our heads around is that in the 6th and 7th centuries, when Islam grew, the notion of secular governance did not exist. Not in Byzantium, where the state religion was Christianity. Not in Persia, where the state religion was Zoroastrianism. Take it back a couple thousand years, and we see the same phenomenon in ancient Israel.

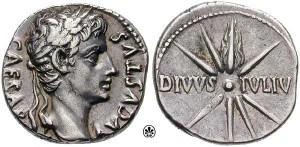

Governance as we know it today in the United States is exceedingly young relative to the history of humanity. For most of our history, religion and politics were indistinguishable. The king, queen, emperor, what have you was also a religious figure. Before and during the time of Jesus of Nazareth, for example, some Roman currency was stamped with the phrase, “Son of God,” referring to the emperor.

Even with our modern enlightened view of democracy, our political systems are still influenced by religion. One easy example: modern Israel is self-defined as a Jewish state whose legislature includes deeply devout Orthodox Jews, their worldview defined by ancient, religious texts. Libraries have been filled on the relationship between Christianity and American democracy. Many people still refer to the United States as a “Judeo-Christian” country, and there is evidence of this in law as well as our national identity. Check out the $1 bill. In who do we trust?

Even today, it’s not possible to totally separate religion and politics. People build and run political systems, and so they inevitability base their decisions, to some degree, on the religious ideas that define their identity and worldview.

Is Islam Inherently Dangerous?

Now, to the evil elephant in the room. The so-called Islamic State.

The devils murdering and raping people in Syria, Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan and elsewhere are evil. No doubt. I’ve read all of the Islamic sacred texts many times, and while there are some things that are unsettling, there’s a lot ISIS is doing that has zero basis in Islam. I know there are people on TV saying otherwise, but they are not speaking from a point of knowledge. They’re speaking from fear, from rhetoric, from ignorance or even from hate.

There are pluralistic, Muslim-majority countries the world over that fit democratic ideas alongside religious traditions. These systems aren’t always perfect, but they are certainly nothing like what ISIS is doing. And perhaps this is the most important nuance for you to take with you. The so-called Islamic State is not the only outcome of a political read on Islam. It’s just one possible outcome, and even at that, ISIS is making up much of their rules as they go.

It’s true, there are passages in Islamic sacred literature that, read in a certain light, might suggest things that make the secular American uncomfortable. There’s stuff in there that makes me uncomfortable. And even though many Muslims might never say it out loud, there’s stuff in there that bugs some of them too. But that does not mean that Islam is itself somehow threatening—at least, no more so than any other religion. (For example, I would direct you to Leviticus and some of the punishments that divine Hebrew law meted out for a range of offenses, many of them minor by today’s standards.)

What then is the threat we face today? Is it Islam? No, that’s far too simplistic. Is it “political Islam?” That’s almost a nonsensical phrase; all religions are to a degree political. Is it “political Islam that governs a caliphate?” Only if that caliphate looks like ISIS and declares war on us (and right now, ISIS accounts for 0.01% of the world’s Muslims).

No, it’s more fundamental than that. Our greatest threat is twofold:

1. Unchecked growth of a violent ideology that draws from but does not define Islam; and

2. An uncontested worldview that pits Muslims against non-Muslims.

We will not be able to address either of these points if we talk, plan and operate from a position of ignorance. Neither the fear-mongering pundits on TV nor the murderers in Iraq and Syria are helping this. They’re making it worse by the minute. We can undercut both of their hurtful messages with just a little information, understanding and communication.

No matter what you believe, I wish you peaceful weeks ahead and a very Happy New Year.

-

Sean

-

Justin Hienz

-

Sean

-

Justin Hienz

-

Sean

-

Justin Hienz

-

Sean

-

-

-

-

-

Sara Huizenga