How hard is it for migrants to cross the southwest border illegally and enter into the United States? That question has long been difficult to answer, but it is one that has become more urgent as Congress prepares once again to consider a broader immigration reform. A new report from the Government Accountability Office gives a surprising assessment – that it appears to have become far more difficult than most Americans realize.

The GAO report is the first to assess the number of successful illegal entries across the border using a method called “known illegal entries,” or “known flow” for short. The number of illegal entries is the key statistic that matters in the debate over border enforcement. The U.S. government has for many years reported the number of “apprehensions” at the border – arrests of those attempting to enter illegally. Last year, that number fell to 327,000 at the southwest border, the lowest since 1972. While the decline in apprehensions from its 2001 peak of more than 1.6 million certainly suggests that many fewer people are trying to cross illegally, it tells us nothing definitive about the numbers who are still successfully evading the Border Patrol between the ports of entry and entering the United States.

“Known flow” is one method for trying to get at this problem. For many years, Border Patrol agents in each of the nine southwest border sectors have collected and compiled data on illegal migrant activity in their sectors. These data include actual apprehensions, but also, estimates made by agents of the number of individuals who made an effort to cross illegally but then thought twice and returned to the Mexican side (“turn backs”), as well as estimates of those who evaded capture and entered the United States successfully (“got aways”). The “got away” number is a combination of individuals who were actually observed but not arrested, and evidence compiled from “sign cuttings,” which are footprints in the desert, broken vegetation, litter, and other clues that help the Border Patrol monitor incursions. These data are then compiled in what is known as the Border Patrol Enforcement Tracking System, or BPETS for short.

The GAO report for the first time pulls together for public release all of the BPETS data for the past five years, though such data exists going back to the 1990s. And the results suggest that getting into the United States illegally across the land border has become significantly harder.

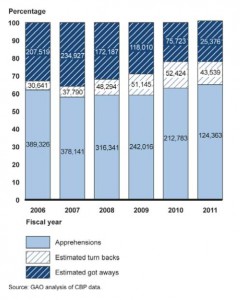

Take the Tucson sector for example, which covers much of Arizona and remains the preferred route for those trying to sneak into the United States. In 2006, the Border Patrol in that sector made nearly 390,000 apprehensions and observed more than 30,000 “turn backs.” And it estimated that there were more than 207,000 “got aways” who entered the United States. In 2011, the Border Patrol in the Tucson sector made 124,000 apprehensions, and turned back another 43,500. The number of successful “got aways,” however, was only 25,376, just more than one-tenth the number who successfully entered only five years before. Put another way, more than 87 percent of attempted illegal entries in Tucson sector were dealt with successfully last year, either because the individual was arrested or feared arrest and returned to Mexico.

Number of Tucson Sector Border Patrol Apprehensions, Turn Backs, and Got Aways as a Percentage of Estimated Known Illegal Entries, FY 2006-2011

The trends are similar in all but one of the nine border sectors, and especially in the large crossing regions in California and Arizona. In Yuma sector in western Arizona, which has become the most heavily fortified and patrolled region along the border, the numbers are especially striking – “got aways” fell from 76,428 in 2006 to just 409 in 2011. But El Paso in New Mexico and western Texas is not far behind, with “got aways” falling from more than 97,000 to just over 1,000. The only exception to the trend is the Big Bend, which covers the remote regions of western Texas, where the number of got aways increased from 1,200 to 2,000.

Across the border in FY2011, the total number of “got aways” adds up to about 85,000 individuals – not an insignificant number, but still quite small compared with the more than 600,000 that were thought to have evaded capture in 2006, and the even larger numbers who likely entered successfully throughout the 1990s and the first half of the 2000s.

The “known flow” estimates are certainly not perfect. They cannot account for cases where an illegal migrant enters completely unobserved by the Border Patrol, and for that reason probably undercount the number of successful illegal entries. Other methods of trying to calculate illegal entry would suggest that the success rate of the Border Patrol is not this high. And there are certainly other ways to enter and remain in the United States illegally, by overstaying a visa or evading detection at a legal port of entry, so that even a perfectly sealed border between the ports of entry would not entirely solve the problem. The Council on Foreign Relations will be publishing shortly a special report by Bryan Roberts and John Whitley, two former DHS officials in the Program Analysis and Evaluation Branch, and me, that will pull together the best evidence available on the effectiveness of border enforcement.

The GAO study is far from the last word. But it is a considerable step forward in trying to assess the progress that has been made in discouraging illegal entry across the border from Mexico.

-

Karen Allen