FOREIGN FIGHTERS

Terrorist Recruitment and Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) Programs in Minneapolis-St. Paul – April 2015

Terrorist Recruitment in Minneapolis-St. Paul

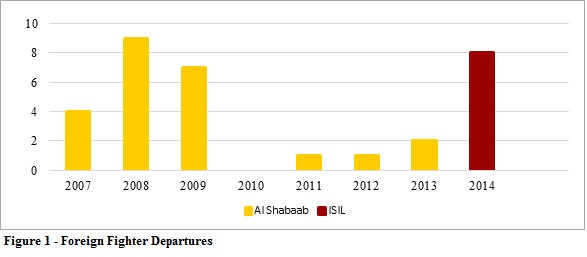

Since 2014, numerous Minneapolis Somali residents have left the United States to travel to Syria to join ISIL. This is an abrupt shift in destination, as previous departing residents went to Somalia to join al Shabaab. Clearly, something changed, not the people vulnerable to recruitment but the benefactors of the recruiters. Presented here are details of recent foreign fighter recruitment efforts that resulted in Somali-Americans joining or attempting to join ISIL and what it reveals about the risk of terrorist recruitment in Minneapolis.

Cases of Recruitment and Departure

In November 2014, we conducted an interview with the family of a young woman who surreptitiously fled to Syria. The family described a jubilant, sociable, articulate person. Recently graduated from high school, the 19-year-old told family she wanted to become a nurse and planned to register for college in January 2015. She had shown no interest in marriage, though it would not be uncommon for her to marry at that age.

In mid-2014, she became involved with a young man and changed her place of worship. Meanwhile, her family noticed a distinct shift in her manner and social interaction. Her mother said that she stopped speaking to friends and acquaintances. She spent much of her time alone in her room, reading the Qur’an, and she reportedly said she wanted to live in an Islamic country and desired more Islamic education.

On a Friday, she told family she was going to a friend’s bridal shower and called later to say she would be spending the night away from home, returning on Saturday. On Sunday, she sent a text message to her mother, saying that she was in Syria.

The story of this young woman closely mirrors that of other young people who have journeyed to join ISIL. In February 2015, London teenagers Amira Abase, Shamima Begum and Kadiza Sultana traveled to Syria via Istanbul to join ISIL. Abase’s excuse to her father for leaving was that she was going to a wedding, a curious (if not suggestive) similarity to the excuse offered by the young Somali woman.

Another example is that of Abdi Nur, who left Minneapolis in May 2014 to join ISIL in Raqqa, the so-called capital of the Islamic State. Nur was attending community college with aspirations of studying law before he became more religious and began proclaiming extremist, pro-ISIL statements.

One might assume that a newfound, strict religious belief is a warning sign that a young Muslim is on a path towards extremism and vulnerability to recruitment; however, in an Islamic family or social group, increased religious activity is not necessarily seen in a negative light. The young Somali woman’s family characterized themselves as religious, able to recite the Qur’an from memory. Her increased religious activity was not a troubling sign but a fuller embrace of the family’s beliefs, which, from the family’s perspective, was inherently good, as it would be for any family holding religion as a core value.

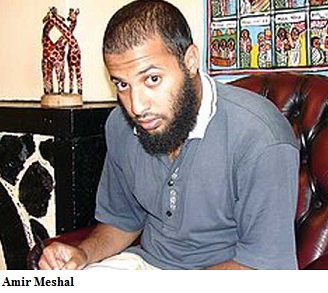

This is one of the principal challenges of empowering families and communities to recognize and disrupt the radicalization and recruitment process. At what point does increased religious activity cross a line from a healthy embrace of belief to a negative, extreme interpretation of religious tenets? It is because of this uncertainty that families may not initially see their young people progressing through the radicalization pathway. Terrorist recruiters can capitalize on this to place an extreme worldview on their targets’ developing beliefs. One example is that of Amir Meshal.

Amir Meshal is an American of Egyptian descent, originally from New Jersey. In 2014, he began frequenting Minnesota mosques. Leaders of the Al-Farooq Youth and Family Center in Bloomington, a suburb of Minneapolis-St. Paul, filed a no-trespass order against Meshal, citing concerns about his interaction with the community’s Muslim youth. Not long after, religious leaders at the Al-Tawba mosque in Eden Prairie called police when a worshipper relayed that Meshal, who was attending, made extremist statements contrary to the imam’s lecture. Meshal has not been seen in Minnesota since.

Amir Meshal is an American of Egyptian descent, originally from New Jersey. In 2014, he began frequenting Minnesota mosques. Leaders of the Al-Farooq Youth and Family Center in Bloomington, a suburb of Minneapolis-St. Paul, filed a no-trespass order against Meshal, citing concerns about his interaction with the community’s Muslim youth. Not long after, religious leaders at the Al-Tawba mosque in Eden Prairie called police when a worshipper relayed that Meshal, who was attending, made extremist statements contrary to the imam’s lecture. Meshal has not been seen in Minnesota since.

One source for this report was intimately familiar with the story of Meshal, as he is commonly asked to help Twin Cities Somali families facing legal problems (including terrorism charges). The source narrated what he had gathered about Meshal’s radicalization and recruitment process, having spoken directly with the young people who met with Meshal.

The process was described to take place over several months. It began with an offer from Meshal to a Somali young man for a free haircut or a free lunch. In an impoverished community with a background of extreme need, such an offer is not flippant. This evolved into a group of four young men meeting weekly to discuss Islam. They deliberately avoided meeting at mosques or in a religious setting. Instead, they met somewhere different each week, sometimes at the family homes of the young men, with family members looking on. There was no obvious reason for concern at first, as the meetings were benign, simply opportunities to discuss the tenets of Islam with young people.

As the conversation shifted from beliefs and practice to the role of jihad in a Muslim’s life, the four young men were instructed not to tell anyone about their meetings, enhancing the relationship and trust between members of the group via the element of confidentiality. Meshal talked about how jihad has been used in the past, in the time of the Prophet and in the growth of the faith afterwards. Having carefully brought his students to a cognitive opening, a point at which one can accept and internalize violent extremist ideas, Meshal asked the question, “Looking at the world today, is there a need for jihad?” To be sure, he constructed a view of the world where his recruits would answer in the affirmative.

This radicalization process ended with direction for Meshal’s recruits to travel to Syria. In July, the FBI stopped an 18-year-old man before he boarded a plane for Istanbul, Turkey. He was destined for Syria, and press reports state that during interrogation, the man identified Meshal as his recruiter.

Reports of how many people have departed the Twin Cities to join ISIL often conflict and lack specificity. What is more, due to the open-source nature of this study, there are limits on the kinds of information the report authors accessed during research; publically available FBI figures are often vague and not easily aggregated. That said, the report authors confirmed that at least eight Somali-Americans have left Minneapolis for Syria since the end of 2013, and there are others who have left who have not been reported to authorities (according to sources). Meshal was identified and rejected by the community but not before he radicalized at least one Minneapolis resident. Logic, as well as source statements, suggests there are more recruiters in the community.

Collaboration between Al Shabaab and ISIL

Some sources for this report said they were confused by Twin Cities Somali youths traveling to Syria. Al Shabaab’s recruiting message had been based on nationalism and genealogy, as well as religion, and multiple sources said they could understand the enduring desire to see their mother country stabilize and improve, even as they disagreed with the extremist interpretation of Islam that al Shabaab espouses. In Syria, however, that nationalistic zeal does not apply, meaning recruiters are attracting young people not based on their country of origin but by appealing to the notion of a global Muslim community and ISIL’s vision of a caliphate and apocalypse.

Sources reported that the recruiters who sent young people to Somalia are the same recruiters now sending young people to Syria. One Cedar-Riverside source, who has known several young people who departed the United States to join a terrorist group, said: “A kid who left [for Somalia] sent a text message to say the new order is to go to Syria. They are using old friends as the messengers.”

U.S. Attorney Andrew Luger concurred with our findings that ISIL has appropriated the al Shabaab recruiting network. What is not yet clear is the nature of the relationship between the two terrorist groups. There are reports that ISIL, via its media outlets, has offered a public invitation for al Shabaab to pledge allegiance to the Islamic State, in the same way that the Nigerian terrorist group Boko Haram did in March 2015. The message also encouraged Abu Ubaidah, the leader of al Shabaab in Somalia, to conduct attacks in neighboring countries. While circumstantial, the fact that al Shabaab recruiters are sending people to Syria and that al Shabaab recently attacked Garissa University in neighboring Kenya suggests that the Somali terror group is edging its way towards a direct alliance with ISIL.

Immigration, Identity and Vulnerability

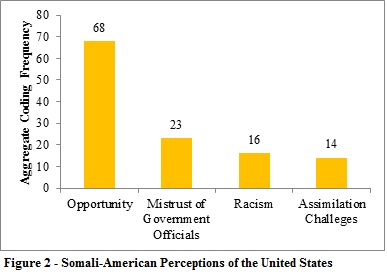

The Somali diaspora following the civil war and famine has thrust a unique Islamic culture and tradition into secular societies. On the one hand, sources overwhelming spoke about the United States as a place of opportunity, and there is a deep appreciation for the refuge the United States offered Somalis fleeing their homeland. Yet, there is a significant mistrust of government at all levels, stemming from a perception that social benefits and support are not accessible to the Somali community in Minneapolis-St. Paul.

Sources expressed insult and anger that, due to their traditional dress and names, they receive undue scrutiny at airports and other public places. Frequent and reportedly invasive police and FBI activity has compounded a sense of opposition with government (broadly speaking). Beyond this, sources reported that the first time they encountered the phenomenon of race relations was when they arrived in the United States. The history of racial discrimination and tension in the United States, experienced particularly by African Americans, is not one shared by Somalis, and immigration to the United States forces an amendment to one’s identity to accommodate racism and xenophobia among the varied ethnic communities in the Twin Cities. These sentiments are encapsulated in a saying several sources offered: “I’ve got five strikes against me, and I just got here. I’m an immigrant. I’m East African. I’m Somali. I’m black. I’m Muslim.” Some female sources added a sixth strike, their gender.

Sources expressed insult and anger that, due to their traditional dress and names, they receive undue scrutiny at airports and other public places. Frequent and reportedly invasive police and FBI activity has compounded a sense of opposition with government (broadly speaking). Beyond this, sources reported that the first time they encountered the phenomenon of race relations was when they arrived in the United States. The history of racial discrimination and tension in the United States, experienced particularly by African Americans, is not one shared by Somalis, and immigration to the United States forces an amendment to one’s identity to accommodate racism and xenophobia among the varied ethnic communities in the Twin Cities. These sentiments are encapsulated in a saying several sources offered: “I’ve got five strikes against me, and I just got here. I’m an immigrant. I’m East African. I’m Somali. I’m black. I’m Muslim.” Some female sources added a sixth strike, their gender.

Each of those points contributes to a shared sense of cultural isolation. In this mix of socio-economic challenges and culture clash, young people struggle to define their identity. A third of Minnesota Somali households are single-parent with children, and while the children adopt English and begin to learn U.S. customs from school, the parents often remain isolated, lacking language skills and knowledge of public services. Young people are left to grapple with the inherent conflict between the lifestyle and worship taught by their elders and practiced at home and the secular, American culture they inevitably share by virtue of growing up in the United States. One source said: “There’s a lot of competing threats to a person’s sense of self-worth. And then, within that chaos of ‘who am I,’ it creates an opening for someone else to come in and kind of say, ‘This is who you are.’”

In this challenging environment, there can be a craving for structure and acceptance, one that is commonly found in America’s urban street gangs. Some young Somali men join Somali gangs, which all sources said present the greatest safety threat to the Minneapolis-St. Paul community. The Somali Outlaws and Madibon With Attitude (MWA), the two primary Somali gangs in Minneapolis-St. Paul, provide a social structure and identity compatible with U.S. culture (though not necessarily its laws). The Somali gang structure is not hierarchical like many U.S. and international urban gangs, though the groups do resemble American gangs in terms of fraternal structure. Seeking relationships and recognition they are unable to find at home, at school, and in the community, these young men are not unlike other ethnicities and nationalities that join gangs to replace critical social elements. In this regard, the attraction to gangs is universal, as they offer understanding and acceptance, becoming the members’ “real” family, the one they can always count on and who will never judge them.

Other young people, however, find structure in an increasingly rigid view of their faith, which may become incompatible with U.S. customs and laws. An increasingly absolute Muslim identity can be encouraged or exploited by a skilled recruiter. Studies show that immigrant adaptation to a new society is best achieved by embracing both an ethnic identity and the new national identity. Foreign fighter recruiters strive to dispel the latter, disrupting an individual’s opportunity to assimilate and embrace the benefits of their new country. Thus, young people in Minneapolis are vulnerable not simply because they have opportunity to congregate in unsupervised spaces but, more fundamentally, because they are young people in a complex environment with limited familial guidance, conflicted and developing identities, and predatory terrorist recruiters.

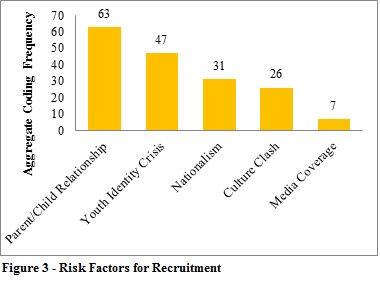

To be sure, there is no single factor responsible for causing an individual to become a violent extremist. There is no terrorist profile, though there are risk variables. In source interviews, the most commonly mentioned risk factor for recruitment in the Somali community is the difficult relationship between parent and child. Obstacles include language barriers between parent and child, long hours for working parents, and a child’s abuse of parental trust. The second most commonly mentioned risk factor was a youth identity crisis. The desire for structure and identity, coupled with a weak parent-child relationship, can make young people susceptible to a recruiter’s message, particularly if they seek the approval of a surrogate family member (in the case of Amir Meshal) or a romantic interest (in the case of the aforementioned young woman). A nationalistic zeal for rebuilding Somalia and immigrant cultural conflict, inflamed by sensationalistic media coverage of terrorist threats, may also make a young person susceptible to a compelling terrorist narrative that leverages these themes.

To be sure, there is no single factor responsible for causing an individual to become a violent extremist. There is no terrorist profile, though there are risk variables. In source interviews, the most commonly mentioned risk factor for recruitment in the Somali community is the difficult relationship between parent and child. Obstacles include language barriers between parent and child, long hours for working parents, and a child’s abuse of parental trust. The second most commonly mentioned risk factor was a youth identity crisis. The desire for structure and identity, coupled with a weak parent-child relationship, can make young people susceptible to a recruiter’s message, particularly if they seek the approval of a surrogate family member (in the case of Amir Meshal) or a romantic interest (in the case of the aforementioned young woman). A nationalistic zeal for rebuilding Somalia and immigrant cultural conflict, inflamed by sensationalistic media coverage of terrorist threats, may also make a young person susceptible to a compelling terrorist narrative that leverages these themes.

Correcting Assumptions

There are two common assumptions made about extremist recruiting that our research revealed to be inaccurate in Minnesota. First, recruits from Minneapolis are not necessarily (or even primarily) lacking in opportunities for a successful future in the United States. Take the example of Zakaria Maruf, relayed to us by one of his childhood friends who knew him before he left for Somalia in 2008.

Maruf was socially popular, athletic and succeeding in school. He was also affiliated with a Somali gang, which at the time called itself the “Somali Hot Boyz.” After graduating from high school, Maruf separated from the gang and became increasingly religious, eventually becoming a teacher at a dugsi in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood. Maruf swapped his gang-centered social structure for one founded on an ultra-strict interpretation of Islam. Based on the findings from this study, it seems clear Maruf did not travel to Somalia because he was poverty-stricken and hopeless but because his identity, based on a narrow interpretation of Islamic beliefs and a vague sense of nationalism, required it of him. As Maruf himself said in a 2009 statement broadcast over a Somali radio station:

Maruf was socially popular, athletic and succeeding in school. He was also affiliated with a Somali gang, which at the time called itself the “Somali Hot Boyz.” After graduating from high school, Maruf separated from the gang and became increasingly religious, eventually becoming a teacher at a dugsi in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood. Maruf swapped his gang-centered social structure for one founded on an ultra-strict interpretation of Islam. Based on the findings from this study, it seems clear Maruf did not travel to Somalia because he was poverty-stricken and hopeless but because his identity, based on a narrow interpretation of Islamic beliefs and a vague sense of nationalism, required it of him. As Maruf himself said in a 2009 statement broadcast over a Somali radio station:

“They want to make it appear as if the people who left or want to leave, those who migrated for the sake of Allah, were people who did not have a life, and they simply want to wrong their name. These are lies and propaganda. It is not possible to brainwash or coerce a conscious, grown man. And where we come from is not a place where people are coerced or brainwashed.”

The report authors did not find any direct link between Minnesota Somali gangs and terrorist recruitment, a view supported by law enforcement sources who monitor Somali gangs and engage the Somali-American community. A law enforcement gang officer said of gang members: “They don’t want that structure of trying to join ISIS or al Shabaab where they have someone telling them what to do. They want to be out there on the block, doing whatever they want to do.”

Sources said that some of the individuals recruited by terrorist organizations may have been rejected from gang membership and thus open to other social networks and beliefs. One source suggested recruiters target gang members, their message being that gang affiliation and action is sinful and the target should conform to Islamic morals; however, no other source mentioned this phenomenon and the report authors were unable to find any evidence of it.

The second inaccurate assumption is that social media has been the primary vehicle for ISIL recruitment efforts in the Twin Cities. In every incident reported during fieldwork, face-to-face interaction was a critical element of the recruitment process. Social media interaction and links to extremist online content reinforce the messages that recruiters offer in person. To be sure, digital communication plays a role in recruitment, but at least in the Somali community in Minneapolis-St. Paul, in-person interaction is irreplaceable.

There are chronic socio-economic challenges in Minneapolis-St. Paul among the Somali-American community. Even as terrorist recruiters hide in the population and seek vulnerable targets, the community is struggling with gang violence, poverty, racism, unemployment, and an ongoing need to assimilate to a new culture and country. While the challenges are great, there are a range of programs and organizations in Minnesota that are geared towards improving the welfare and quality of life of the Somali residents and countering the violent messages of ISIL and al Shabaab. Read the next section.

Report Sections